FACULTY OF HUMANITIES

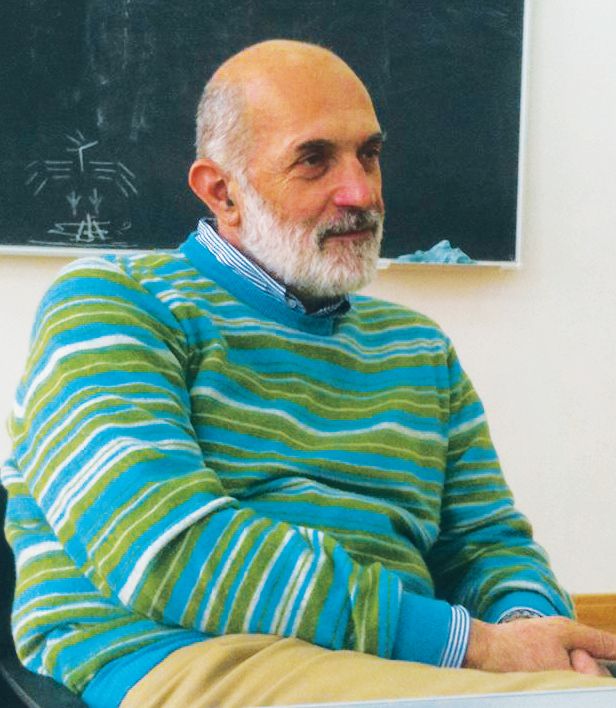

Ethnology – A Discipline for Resolving Ethnic Conflict

In Georgia’s southwestern region of Samtskhe-Javakheti, there is a high percentage of ethnic minorities. Issues such as the forcible deportation of Meskhetians remain a ‘dark example’ in the history of Soviet Georgia. The country still carries an important moral responsibility to make reparation to these people for the way they were treated by the Soviet Government of Georgia. This is why the new book by Dr. Roland Topchishvili, The Ethnic History of Samtskhe-Javakheti (2013) has evoked great interest within Georgian scientific circles as it treats the complex ethnic history of Samtskhe-Javakheti, including the impact of Moslem and Turkish culture on Georgian people of the region.

The author traced the migration routes of Georgian people, their historical and demographic processes, the settlement of various ethnic groups in Georgia and the relationships between all these populations. The process of converting Georgians to Islam not only happened in the Samtskhe-Javakheti region but elsewhere in southwest Georgia, in areas occupied by the Turks. For example, today Imerkhveli Kartvelians call Shavsheti Turks from Turkey “Overturned Georgians’’ i.e. assimilated Georgians. This process of Islamization was common in the Ottoman Empire and one of the methods for encouraging populations to convert was the imposition of higher taxes for non-Turks or non-Muslims, for example for Georgian peasants, who were Christian. Eventually, they had to convert to Islam and every Moslem was considered a Turk in the Ottoman Empire. Over time, many Georgians also lost their mother tongue.

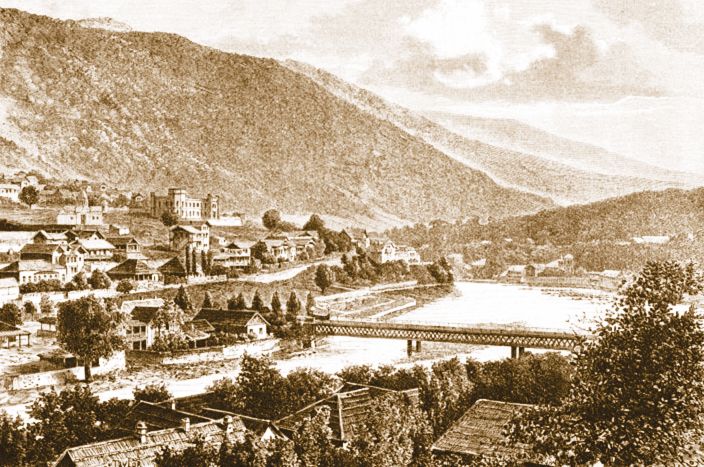

Borjomi XIX Century, the newspaper "Droeba"

Other studies on the Islamization of parts of Georgia have been made, but this study is the first to include relevant census data collected by the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century, specifically census and family listings gathered in 1860, 1873 and 1886. The book is divided into two parts. Part I is based mainly on archival and ethnographic sources, and discusses Samtskhe and how Georgians were impacted by Islamization and the Turkish cultural hegemony. Part II is dedicated to issues concerning the populations of Javakheti. The author traced where the Georgian people of Javakheti migrated to. In the 17th and 18th centuries many Georgians from Javakheti migrated to the Kartli region. During this period, in every other village of Kartli, one encountered Georgian surnames of Javakhetian origin. Many locals in Kartli know that their ancestors came from Javakheti.

Although the book appears at first to be the unexpected outcome of years of study, in fact the author has studied Russian census data since he was young. This data were collected by Russian czars, and included unique information onthe religious and ethnic situation and migrations within the former Russian Empire, thus it is of great importance for the study of Georgian ethnic history. “Despite the fact that these people were already Muslimsin the 19th century, they kept their own ethnicity. In the census data studied, they would write ‘Georgian’ in the nationality graph, and although they were referred to as ‘Oghlob’ (their names and the names of their fathers) in the surname graph, they still had their Georgian surnames written beside it, showing that these people were ethnically Georgian.”

This data were taken from 19th century Russian archives. Georgian historical documents from the 17th and 18th centuries were used for a specific part of the book dealing with the migration of the Javakheti population to Kartli. Their migration is confirmed in the Russian census of 1818, where families had kept written documents noting that they had moved to Kartli 100, 50 or 20 years before.

The author presented his work on the Islamization of Georgians at an international conference organized by the association ‘Tolerance’ on June 1, 2013 in Tbilisi.Using archival materials and ethnographic data from his book, he presented specific surnames for detailed discussion. Other recent research by Dr. Topchishvili investigates the lives of Georgians residing on Turkish territory. He visited every single village in Shavsheti, Tao and Klarjeti and-- accompanied by his colleagues--discovered places where the Georgians migrated to in 1878, and where they currently live. Despite the fact that people here over 40 years of age speak Georgian while people under 20 don’t, they all have kept much of their ethnic identity. The scholar urges Georgian society to do everything possible to ensure that Georgians residing in Turkey maintain their Georgian language, and points out that TSU can support this initiative.

He is also investigating Georgian-Ossetian cultural-historical relations, and his research on ethno-historical origins of Georgian names-surnames isunique. In general, according to Dr. Topchishvili, ethnology is the discipline that examines all issues concerning human populations. It studies lifestyles (e.g. urban, rural, age-based), group characteristics, cultural aspects of family and institutions, as well as relations between ethnic groups. “Ethnological studie sare of great practical significance as well asof theoretical-educational value. If Georgian ethnologists had studied Georgian-Abkhazian and Georgian-Ossetian relationships we might have avoided the current conflicts. We should thoroughly study the ethnic groups living in Georgia in order to be able to help settle relationships with minorities living here. We should explore each problem and point of view of these groups and provide the Georgian government with recommendations to be considered for policy and action.”